The second two programs of the Boris Charmatz’s Three Collective Gestures series on offer at the Museum of Modern Art were more easily accessible to contemplation and hence to enjoyment than the first (see my previous review in this column). Levée des conflits extended/Suspension of Conflicts Extended (October 25-27, 2013) was performed in the Atrium with its natural light and with spectators gathered on all four sides. Twenty-four dancers worked within the closely circumscribed movement material of 25 choreographic items. Charmatz’s inspiration can be seen to derive from what dance critic and historian Sally Banes identified as “analytic postmodern dance” of the 1970s, which she characterized as “reductive, factual, objective … emphasizing choreographic structure and movement per se” (Terpsichore in Sneakers p. xx-xi). It began as solos but soon led to groups of diverse individuals working their way ultimately into a tight circle yet remaining independent and autonomous as the soundscape became increasingly violent and apocalyptic. The diversity of movement patterns, body types, and approaches to performance was engrossing to observe. From the initial calm there was a buildup not only of numbers but of tension yet this occurred without acceleration. The shifting soundscape by Olivier Renouf, along with a patterning shift in space, was largely responsible for the dramatic change. Charmatz is a wonderful curator in his selection of dancers and his ability to communicate his vision to them.

The program note presents Suspension of Conflicts Extended as a durational piece: “a hybrid form of choreographic exhibition and installation”. While it is true that one can observe it from many angles and, due to repetition, see the same elements in multi-faceted ways as if the dancers were sculptural objects, and while it is also true that almost all the performers appeared to be exhibiting the movement rather than to “performing” it (although exhibition is itself a performance), I was not convinced this work engaged in any particular way with the relation of dance to the museum as much as it was a choreographic work felicitously placed in a museum site.

It was the final work of the series, however, Flip Book (October 1-3, 2013) that reengaged with the theme of dance and the museum and added another layer to the relation of contemporary dance to its own history using the museum as a backdrop. For this work MoMA constructed a stage platform and provided very appropriate lighting and seats on risers, which agreeably transformed the Atrium into a space for performance without it being in any way an explicitly proscenium situation. It was interesting and refreshing to experience the Atrium in this different way so complementary to the performance.

Taking as a point of departure David Vaughan’s book Merce Cunningham: Fifty Years (1997), which covers the choreographer’s career by decade with many beautiful photographs as well as text, Charmatz has explained the genesis of his idea: “It occurred to me that this collection of pictures was not only about his projects, but that it formed a choreography in itself that had little to do with the work of Cunningham except inasmuch as it replicated certain images. I started to wonder if we could invent a single piece from this ‘score’ of pictures – if the book could in fact be performed from beginning to end.” The photograph becomes a quote or citation from which to generate a new work, much in the spirit of the recreation of Vaslav Nijinsky’s Afternoon of a Faun – d’un faune . . . eclats — by the Knust Quartet in France (2000). That Charmatz, formerly a member of this group, took this approach makes sense because the Quartet was similarly engaged in finding what dance, removed from us today, could mean now. This implies transformation. The assumption is that a gulf separates the then from the now. As Isabelle Launay has written in an illuminating article about the Knust Quartet, contemporary French dance was involved during the 1990s in a critique of the oral transmission of dance. “The challenge of citation to the prestige of oral person-to-person transmission of a dance has introduced a new way for contemporary artists to relate to and re-embody past works” (Isabelle Launay, “Citational Poetics in Dance: … of a faun (fragments) by the Albrecht Knust Quartet, before-after 2000,” Dance Research Journal 44/2 (Winter 2012)). In Flip Book, the citation is the photograph, the fragment of evidence from which to fashion a new work. While Flip Book appears to be a hommage to Cunningham it bears in actuality very little resemblance to his work.

So, the point is not at all to replicate Cunningham either in movement or as a still image and for this reason Flip Book qualifies more as a reenactment than a reconstruction. As Rebecca Schneider has remarked in her book Performing Remains: “The ‘still’ in theatrical reenactment – especially in the heritage of tableaux vivants – offers an invitation to constitute the historical tale differently” (London: Routledge, 144). While French dancers of the 1960s and 1970s who saw the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in France at its first appearances there in 1964, 1966, and 1970, made the obligatory pilgrimage to New York as part of their formation, French dance since the 1980s has been standing on its own two feet. It is more than anything else this distance to which Flip Book testifies, even in a rather tongue-in-cheek manner by pretending that movement can be extracted from still images.

And perhaps this is, after all, in the avant-garde spirit of Cunningham. Carrie Noland has recently written about the Merce Cunningham Dance Company Legacy Plan, asking: “Can a corpus of controversial works and ideas be preserved for posterity without betraying the fundamental impulse of an intentionally self-exceeding experimental art?” (Carrie Noland, “Inheriting the Avant-Garde: Merce Cunningham, Marcel Duchamp, and the ‘Legacy Plan,’” Dance Research Journal 45/2 (August 2013), p. 85). Noland also explains that Robert Swinston, Director of Choreography of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company since Cunningham’s death, “believes that accuracy in reconstruction is essential” (p. 88). From this perspective, Charmatz’s quotations of the photographs would be considered a slight. Indeed, Alastair MaCauley, in his review of Flip Book, has called it “an act of desecration” (“Using a Familiar Device to Dance out of the Past: Page by Page,” in The New York Times, November 5, 2013).

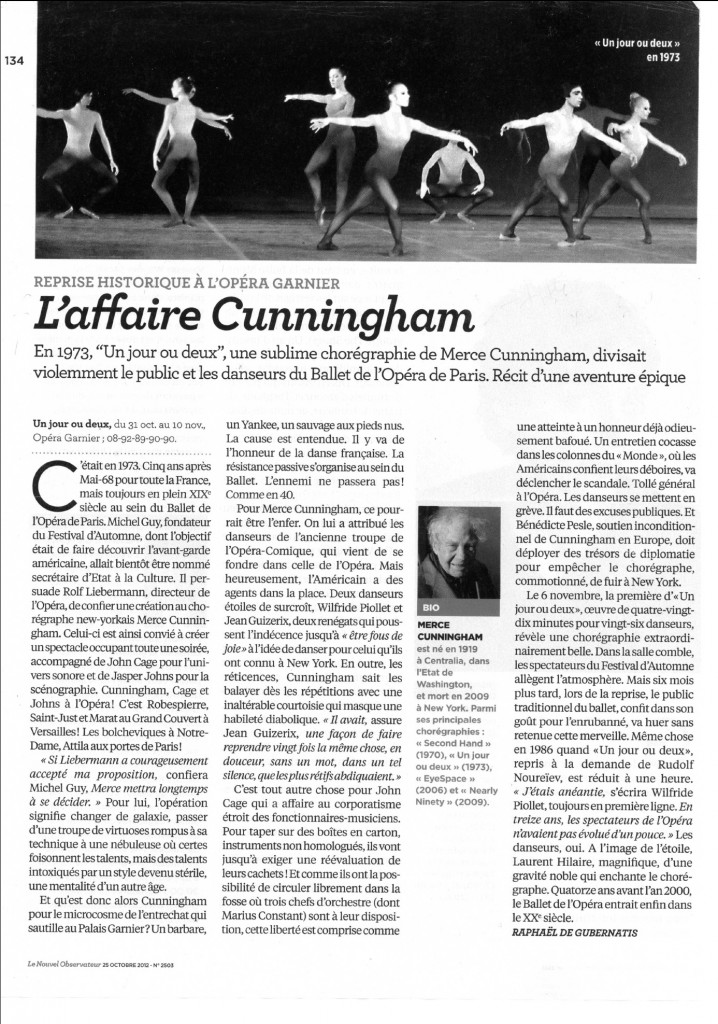

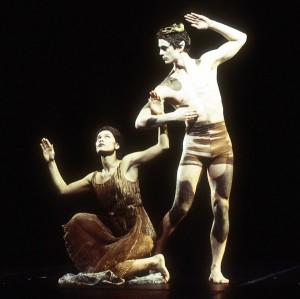

So, it is interesting to consider Flip Book in the context of two other events in France that also brought Cunningham to public attention in the last year. First, the restaging of a Cunningham work originally commissioned by the Paris Opera in 1973: Un jour ou deux. In an article entitled “L’affaire Cunningham” (Le Nouvel Observateur, October 29, 2012), Raphaël De Gubernatis recalls the daring move to invite Cunningham, John Cage and Jasper Johns to create an evening-length work for the Paris Opera Ballet. Musicians were outraged at Cage and the dancers threatened to strike; the public was turned off. Also in 2012, but unnoticed by the grand public, the world of French contemporary dance was convulsed by the appointment of Robert Swinston as director the Centre National de Danse d’Angers (CNDC), replacing Emmanuelle Huynh, another alumna of the Knust Quartet. A letter sent to the Mayor of Angers (April 26, 2012) protesting this appointment and signed by 667 dancers and choreographers, states: “It seems to us that this change, if it happens, would in fact be regressive, especially if its principle idea is to concentrate on the teaching of a single technique, one aesthetic, one name. Of course, we respect the work of the formalist structure developed by Merce Cunningham in contemporary dance history, but to make it the principal choreographic ‘motor’ of a school and a national choreographic center seems neither opportune nor appropriate. Our dance has never been constructed around the figure of the ‘master’, but instead by a way of thinking, making thought into action, not focused on a single heritage.”

I saw Flip Book twice, and given the variations in the sound score both performances were substantially different. In the second, the dance seemed to come to life among the performers, but also became further distanced from Cunningham’s style to a large degree. Although the sound was at no point Cagean, in the second iteration it was particularly unlike Cage. Premiered in 2009, the year of Cunningham’s death, Flip Book could be considered symptomatic of the situation of Cunningham’s legacy in France today. The passage of time has burnished admiration of his choreography at that bastion of conservatism that is the Paris Opera, but has engendered ambivalence toward the necessity for technique — for the “getting it right” under the watchful eye of the master — that one choreographer’s style inevitably imposes, and with which Cunningham has become associated as a modernist master. It is precisely this ambivalence that Flip Book exemplifies and that, like it or not, is actually its subject.