by Juliet Neidish

“Cédric Andrieux” (2009) is the name of the piece created for and performed by the contemporary French dancer Cédric Andrieux. This solo, conceived by the internationally famed French choreographer and conceptual artist Jérôme Bel, belongs to his series of autobiographical stagings, each a contemplative look at the career of the dancer who performs the work. In “Cédric Andrieux”, we spend an intimate 80-minutes with Andrieux during which time he tells us his story and also dances selected movement and short pieces of choreography. In other words, this is a spoken piece, with dance interspersed as visual aid.As Andrieux describes to us, Bel asked him to write the text and to choose the movement. Over a period of time, raw and revised text were e-mailed back and forth. Bel therefore, designed the structure and edited the text, while Andrieux wrote and choreographed. Andrieux enters wearing studio workout clothes and microphone headset, carrying a dance bag and water bottle. Standing calmly, center stage, he begins to tell the story (all in the present tense) of how he began to dance. He speaks in a matter- of- fact monotone, physically and vocally withdrawn from and non- reactive to even his most humorous comments and emotional summations. The 35-year old dancer tells us how he came to work in the companies of Jennifer Muller, Merce Cunningham and the Lyon Opera Ballet. He shares with us what he learned about himself while developing this piece. Before beginning to dance, he either moves to a different spot on the stage, or warns us that he is going into the wings to change into a costume that he has already introduced us to, thereby demarking the dancing space from the talking place.

A work like this reveals a lot about the day- to- day challenges of a dancer. In a particularly charming segment, he tells us what was going through his head while doing the never changing daily warm-up designed by Cunningham that Andrieux executed relentlessly before each rehearsal for the 8 years he was with the company. While fully demonstrating the exercises, he commented for instance on which section always hurt his body, or which one was so boring that he inevitably found himself thinking about what he would eat for dinner that night. Incredibly interesting was his blow by blow of how Cunningham actually choreographed in his latter years when he was too old to show the steps to his dancers. As Andrieux told it, Cunningham, sitting on a chair, would use only words to explain the movement that he had already made up on his special computer program. First he would describe what the leg would do (swing leg in front, place down in plié). Then what the torso would do while the leg was doing the previously set movement (flat back parallel to floor). Lastly, he would describe the arm, for which there were pre-classified positions (for example, round, low, side or straight high, diagonal). Finally, the dancer would have to painstakingly put all these directives together step by step to make movement. This seemed like the most counter-intuitive and cerebral method imaginable for trying to learn a dance. Andrieux also spoke of his insecurity and emotional frustration as a dancer for Cunningham, who was known since the founding days of the company to rarely give his dancers feedback, corrections or encouragement.

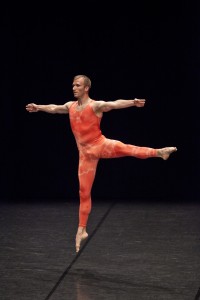

What was extremely enlightening was how grandly subjective autobiography can be. When I watched the section from the Cunningham repertory (extracted from “Biped”) that Andrieux had chosen to illustrate the technique, it was a selection that was quite a-typical of Cunningham’s oeuvre, requiring tight, hurling jumps starting from a crouched position of the body that hovered close to the floor. It almost did not look at all like a Cunningham sequence and I found that choice of selection rather odd until I realized that the dance segment was performed precisely at that point in the piece in order to demonstrate how physically difficult and frustrating the Cunningham work was for much of the duration of his stay with the company. My realization became even clearer when he chose to perform a section from a piece by Trisha Brown that he had danced in the Lyon Opera Ballet post Cunningham. After telling us how much kinder the work of Brown was to his body, he chose to show something from her more Cunningham-derivative period, which he did indeed dance with a lightness and ease that was missing from the “Biped” segment as well as from the short solo from Cunningham’s “Suite For 5” which Andrieux said he was eventually able to feel freer in over time.

“Cédric Andrieux” and the other works in Bel’s autobiographical series (Véronique Doisneau (2005) was the first), ask the dancers to tap into the wide range of skills that are honed during the training of a strong and complete dancer. These pieces reveal clearly that when separated from the act of dancing, one can see that a seasoned dancer has acquired skills in acting, timing, communication through body and voice, the crafting of details and of finish, and perhaps of most importance, an ability to tap into and access resources from a vast imagination. In watching dancers perform, what is not always obvious is that despite the look of ease, excellent dancers are in fact using all of these skills when they dance.

Andrieux’ performance skills are riveting during the segment he performs from Bel’s, “The Show Must Go On” which he learned during his tenure at the Lyon Opera Ballet. It was at this time that he first worked with Bel. In this piece, Andrieux informs us that there are no steps, no set choreography, and therefore no physical pain or stress on the body. In it, the large company was asked to stand onstage and mimic in their own way the words to various pop songs. To Sting’s song, “Every Breath You Take”, Andrieux walks to a place downstage left and does not move from there. While the song plays, we hear the famous lyrics, “Every breath you take/Every move you make/Every bond you break/Every step you take/I’ll be watching you” while Andrieux gazing outward, remains stone still except for miniscule moves of his eyes which turn his head ever so slightly and very, very slowly to pan the theater from one side to the next. This is Andrieux thus, “watching” the audience. I say this is riveting because at once he is doing so little and so much. Holding our gaze, he is performs with an intensity unlike anything we’ve seen so far while hardly moving his body. Compared to the calm, deadpan of the overall storytelling, mixed with the full-out rendering of the prior complicated choreographies, this final segment, though intended to appear pedestrian, is one of complete artifice which smolders, seeming like it is about to explode from within. And yet what is actually revealed is that from out of his tense, buzzing inner core, all of a sudden comes a brightly glowing smile that radiates from a face that we now realize despite having made us laugh and chuckle, has not yet ever smiled until now. This was a tour de force finale to a piece which took its audience happily on a life journey thanks to the skill, inventiveness and rigorous collaboration between two artists. A special thanks to the French Institute Alliance Française along with the partnership of France and New York-based presenters of the “French Highlights” program, for offering this free performance at the Florence Gould Hall on January 10, 2013.